Forlorn Utopia

Review of Construction of a new body, a group exhibition part of the mini-art festival with the same name, Kurant Visningsrom, Stakkevollan Auditorium, Tromsø, 15.11.2019 – 17.11.19

Written by Marion Bouvier

Over three days, the artist-run space Kurant Visningsrom made its home in the Stakkevollan Auditorium, located in the housing cooperative Utsikten – a 20 minutes bus ride outside the city center of Tromsø. During the mini-art festival, which the exhibition Construction of a new body was part of, Kurant made great use of the peculiarity of the space. The first thing that stands out when entering the auditorium is the room itself. The massive stairs structure, the strange combination of office colors and construction materials, and the wall on the left side of the room: a façade of raw rock, lined with white veins, from which water oozes and softly trickles down to the sandy ground. In itself it constitutes an outstanding element of the exhibition, making the otherwise bureaucratic auditorium more akin to a grotto or a temple to old gods.

Site-specific support

Lending support to the rock wall is Emelie Ieremia’s site specific installation entitled Lover Consuming Lover (2019). The erotic appeal of that title contrasts with the minimalistic display of hard materials: wooden beams and constructions, ropes, and satin pillows filled with hard-set marble dust. These impersonal structures come to life through the evocation of tenderness that they, almost miraculously, summon: they support each other, not so much literally as metaphorically, highlighting each other’s presence and form, reaffirming each other’s contours and physical quality by their jarring association.

Ieremia’s artwork thus takes a formalist approach to the title of the show itself: it evokes to me the current of architecture-can-change-society of the 18th century utopian movement by constructing structures in order to create ideological spaces, such as the Saline royale d’Arc et Senans, an “ideal city” designed by Claude Nicolas Ledoux. But in Ieremia’s architectural world the ideology is not utilitarian but purely conceptual; and contrary to the idyllic city of her utopians precursors, the one she depicts seems to have fallen apart: maybe abandoned and left to ruins, while its bits and pieces are left alone to fend for themselves.

Dystopian landscapes

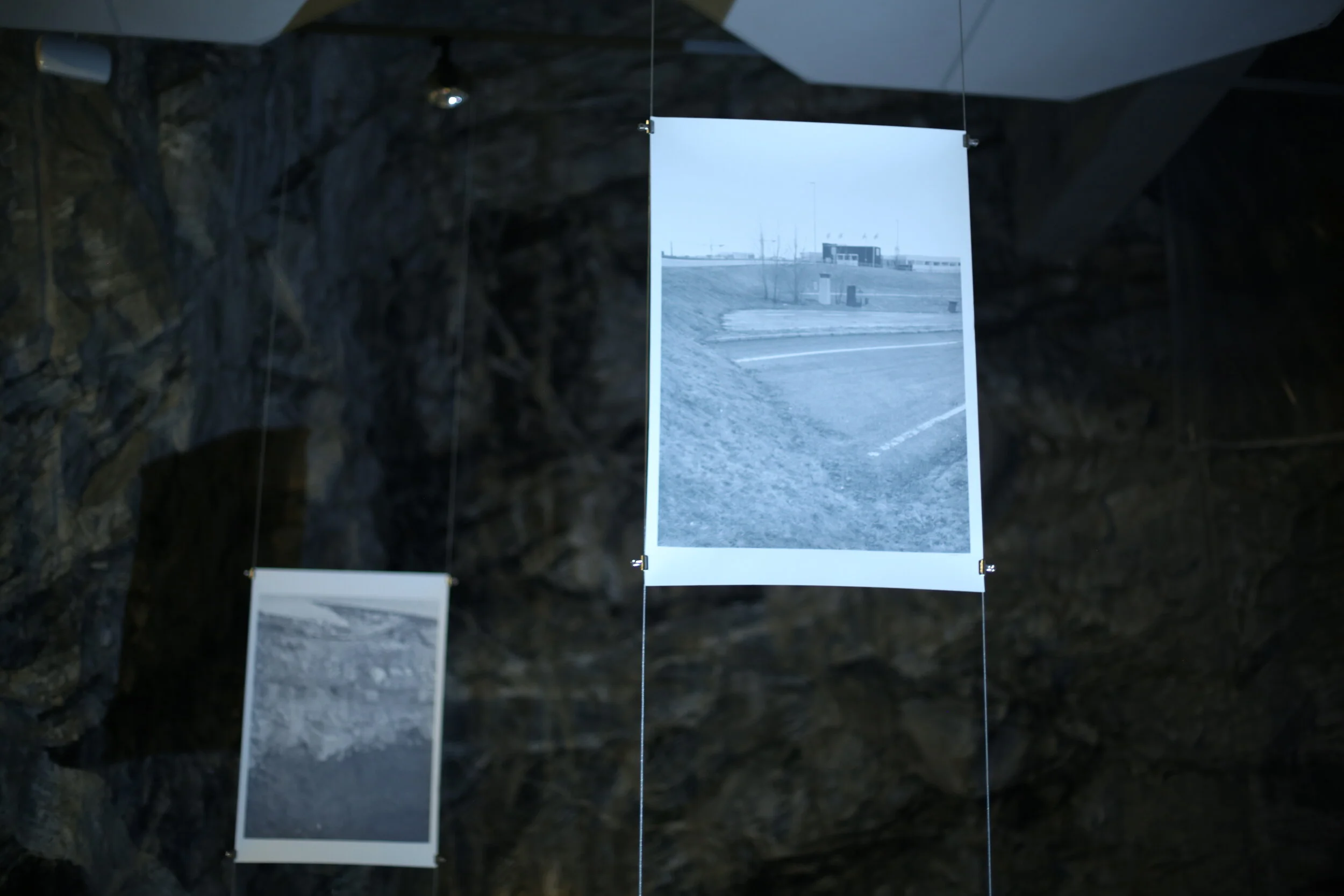

On top of the auditorium stairs, close to Ieremia’s work, another valuable addition to the exhibition is Linn Horntvedt’s photographs of construction infrastructures in black and white, silk-printed on paper. Finne sted, finner sted, funne sted (2015) (to take place, taking place, taken place) is an obvious fit for this particular location. These photographs display what looks like a half-demolished roadside or construction lot, as well as a deserted parking lot that seems to have just been dug out of nowhere. Spaces affected by Man, but also left to their own devices, empty of humans. One could imagine them the scene of a post-nuclear disaster in the future, but also the typical landscape of post-industrial towns that have lost their polish in a not-so-distant past. If the work of Horntvedt doesn’t feel particularly innovative in its execution, it does find its place very well in the site-specific characteristic of this group show.

Although very different in style, the HD film installation You Belong in Content (2017) by Aaron McCarthy echoes a similar feeling of forlorn utopia. Consisting of a parachute and several screens with a 3D animation video, this installation stands against the base of the rock wall, just before the auditorium itself. Futuristic in substance, it tackles the idea of utopia from what we could call an escapist point of view. On the screens, we see two hands forming fists, as if maybe holding video game controllers, on the foreground, and idyllic virtual landscapes in the background. A soft, almost hypnotic music plays, with the chirping of birds occasionally heard. “I was dreaming,” says the text on one of the screens: and indeed there is something eerie about this work, as if one got lost in the virtual world, or chose never to exit it. The whole piece blends itself surprisingly well in the auditorium, giving it a feel of a post-apocalyptic underground shelter where its last inhabitants would be living in virtual reality.

Human failure and post-anthropocentrism

Another dystopian work is Agniezka Mastalerz’s video work H (Reconstruction of Position) (2018) A girl is shown alternating between 20 positions, her face devoid of emotions. The 20 positions are reconstructed from archival photographs of 20 Jewish children who had been used for medical experiments by the SS doctor of the Neuengamme concentration camp, and who were killed in 1945 as the liberation armies were reaching Hamburg. Thus the digital video loop reminds us of the tragic way in which superstructures and ideologies can constrain the individual body.

Blending past and future in a delicate and slightly melancholic way, is Maija Liisa Björklund’s Reconstruction of a future memory (2019). On a light table, it shows an unfinished drawing of a landscape, and nearby lays a hand-drawn map with instructions, as well as a poetic text. Through these, the artist explores a possible future for an existing construction plan put on hold. This dreamy work shows human failures as a potential for new growth, which makes it one of the most “realistic” and hopeful pieces of the lot.

The video work Upon meeting another sentient being (2019), by Nicolas William Hughes, brings up another interesting aspect to the show: the idea of sentience, which in turns evokes the possibility of a post-anthropocentric world. Hughes films a wood ant colony and a voiceover explains that an ant hill functions as a network composed of many parts, which in its entirety is as sentient (able to feel, perceive or experience subjectively) as a human being. The making of the video feels clumsy towards the end when it shifts from the micro focus on the ant colony itself to a macro frame where we see the artist himself approach the nest, surely stepping on many ants in the same time, and laying his hand on it to “make contact” with this other form of sentience. This anthropomorphic way of greeting other sentient beings slightly undermined the points previously made.

A collective body in search of its identity

There are some minor glitches with some of the works that seem individually at odds with the rest. One of these is Let’s make it super premium (2018): a 6 minutes film by Maren Dagny Juell, screened on a tablet in the entrance corridor. It shows an older white man declaring affirmations based on actual quotes that the artist collected from video tutorials by “Person Trainer instructions and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs.” It is a valid critique of how capitalism has established itself as one of the strongest utopias in recent centuries, shaping our psychology, our habits, and even our dreams; and how the Internet is the perfect tool to spread that ideology. Yet its strange position in the entrance hall, almost “greeting” the visitor with its clinical monologue, makes it feel slightly out of context, and there is a sense of lack of aesthetic connection with the rest of the body of works–which in turn may explain its ‘outsider’ placement.

For different reasons, Crayfish (2019), a digital film by Johanne Bockmann, feels a little too far from the main thematic. It shows a crab coming out of its shell in an endless loop, and is, according to the exhibition leaflet, “a spiritually oriented portrait of [the artist’s] friend Ingeborg.” Screened on one of the TV monitors, it seems somewhat parachuted in the exhibition without really deepening the reflection around utopia/dystopia or about systems/users. With its soft tones and human-free look, it is however aesthetically more in tune with the location itself, which allows it to blend rather seamlessly in the surrounding dystopia.

A conversation to be continued

Overall, Construction of a new body feels coherent and thought-provoking, as it offers an interesting and timely reflection on the concept of utopia and the relation between systems and their users. The exhibition features some notable works, and its use of the Stakkevollan Auditorium was an excellent choice. In addition to the exhibition Kurant also presented several events; a flag making workshop led by Line Solberg Dolmen, a walking performance by Tanya Varbanova, as well as the Tromsø Folkekjøkken (Tromsø People’s Kitchen) and a film program curated by Kurant with a little help from Sarah Schipschack.

However, in relation to the overarching theme of the event, I would have liked to see more works hinting at “protopia”, a neologism that describes a realistic utopia based on improvement of the status quo rather than a quest for perfection, and an important concept in dealing with climate change. I felt that the dystopian tone of the exhibition evoked more the destruction of body than construction, and introducing protopia into the discourse could have added a more constructive layer to the show.