Looking for the origins of fear: Polina Medvedeva on making her sound installation ‘A Knock From Below Heard At The Bottom’

Interview with Polina Medvedeva, Kirkenes, 2023.

Around the time of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the Dutch-Russian artist Polina Medvedeva started thinking about self-censorship, intergenerational fear, as well as collective responsibility and the factors that led to this war. One year later, her sound installation ‘A Knock From Below Heard At The Bottom’ was presented at Barents Spektakel 2023. Eleni Ieremia spoke to Medvedeva about how this piece came to be.

The 2023 Barents Spektakel festival opened on 24th February, at the one-year anniversary of Russia´s invasion of Ukraine. The festival is held in Kirkenes, usually known as the capital of the Barents region, and from there lies the Russian border only a few minutes drive away. The festival is organized by the curator-collective Pikene på Broen who chose the concept of trust to be this year’s festival theme. What can we trust when we live in a time of information war and competing narratives in the media and across the border? Can you trust your neighbors? How do you know if you can trust someone? These are some of the questions that were brought up and discussed through art exhibitions, performances, debates, workshops, theater plays and concerts.

Visiting the festival, I was reminded of what the humanist thinker Hannah Arendt says about collective guilt, shared responsibility and why one tends to disassociate oneself from civic or collective responsibility in times of war and economic hardship. I wonder if Arendts' thinking could be used for discussing narratives of guilt and collective responsibility in war today. Especially, when there is a tendency to invoke collective guilt, and as Arendt put it; “where all are guilty, no one is.” This does not imply that no one is responsible; you can be guilty of not practicing your civic and shared responsibilities.

The festival exhibition took place in the old fire station, in Kirkenes. During the Second World War, when this city was heavily bombed, the fire station was one of the few buildings that were left standing. The Nazi Germany had used the fire station as a military hospital during the occupation. The building has now lost its function as a fire station, as a school, as a hospital, municipality office etc, and been left empty for some time. This year's venue for the festival exhibition focused on artists that explore listening in different ways in their work. According to Pikene på Broen, listening could work as a tool in creating trust, understanding and new perspectives.

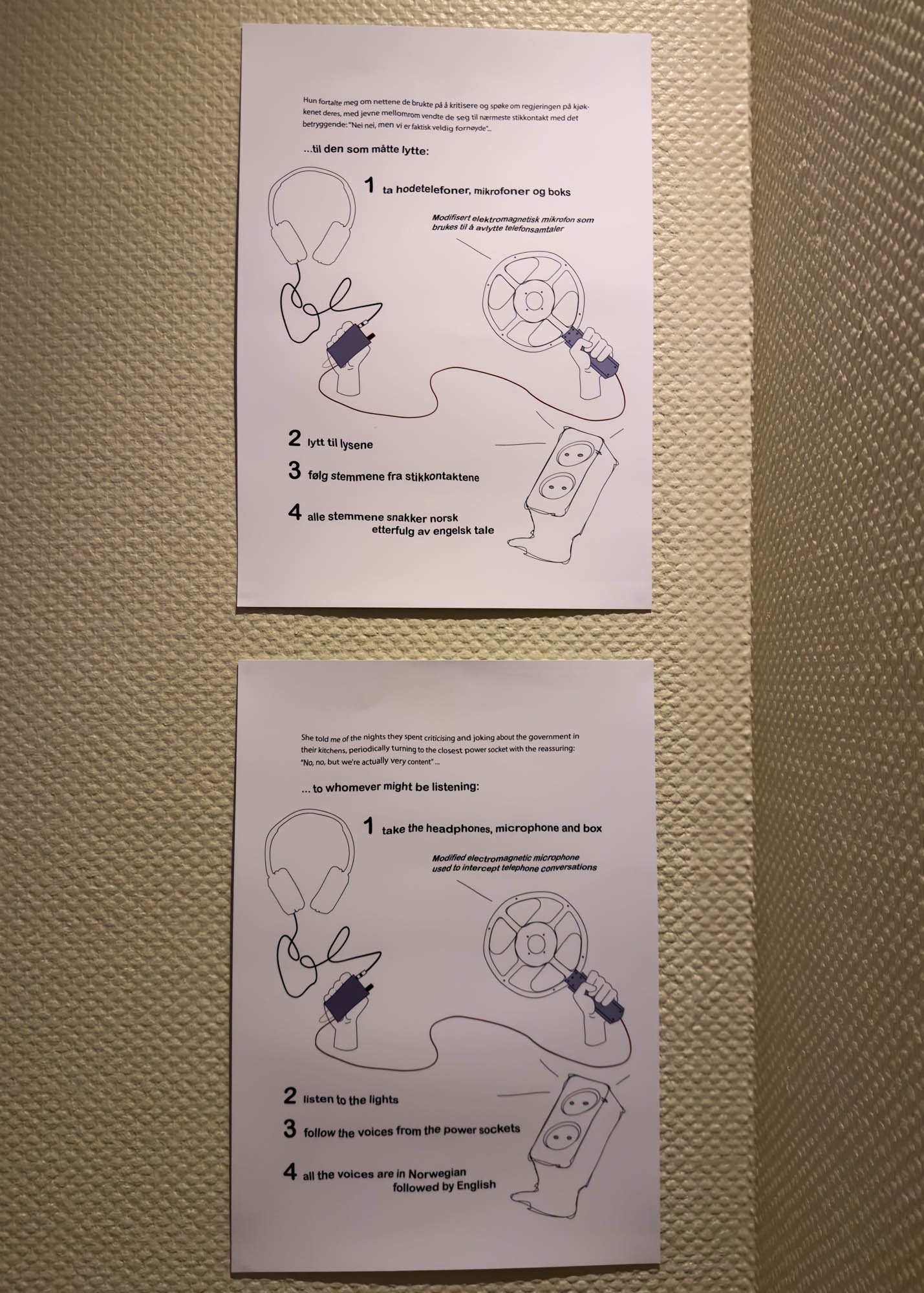

I got the chance to interview the Dutch-Russian artist, Polina Medvedeva, who is one of the artists participating in the festival exhibition. Her immersive and interactive sound installation, A Knock From Below Heard At The Bottom (2022), was shown in the cantina in the former fire station. It consists of an assemblage of conversations and stories that allows one to listen through an electromagnetic microphone when you carry it while walking around in the room. As you approach the transmitters on the walls you hear a buzzing noise and suddenly voices appear in your headphones. The transmitters are embedded in what resembles power sockets but are actually made out of porcelain and it looks as if someone had tried to melt them. I understand this symbolic gesture differently when I read about the background to the title of the work, which cites to the wiretapping and placing of bugs in power sockets by the KGB in the Soviet Union, and the fear and paranoia of being overheard when making critical statements towards their political leaders. There was a saying and a joke that you should lean over the power socket, where bugs could potentially be placed, and make sure to the people listening that you were only joking.

From each of the twelve power sockets you hear conversations, such as a phone call between a Russian soldier and his wife. They talk about a pair of sneakers he had stolen from an Ukrainian home and the wife is telling him to loot everything he can get hold of (the conversation was intercepted by the Ukrainian Secret Service).

The sound installation acts like a non-linear story without an end point. When I walked around in the room I felt like I became a detective, or the peeper, listening to them on the other side of the wall or the other side of the border.

Medvedeva´s work invites you to interact with the installation and requires you to be active to be able to fully perceive it. This creates an engagement from your part and with that an opportunity to spend time to listen and reflect on the critical questions that are brought up in the work; the horrific events that are taking place in the war in Ukraine, lethargy in Russia today, family conflicts and activists who resist and the weakening of civil rights.

Eleni Ieremia: I would like to start the interview with an odd question. Were you a weird kid?

Polina Medvedeva: I was a bit of a boyish-girl, climbing in trees and playing with the boys until that age when it was not seen as appropriate anymore. I also did get kicked out of two kindergartens.

EI: Why?

PM: This is going to put me in a bad light. I guess I was a bit of a bully as a child. I remember one child would sit and build a castle out of wood or something and I crushed it. I was also cursing a lot in kindergarten and you are not supposed to do that. Every time you cursed, the teachers would clean your tongue with soap.

EI: It seems like you reacted against something and had the need to disrupt order back then. You moved from Russia to the Netherlands as a twelve year old. Do you think you cultivate an outside perspective when not belonging to a fixed culture or identity?

PM: I think for example that the discourse that is situated in Russia right now is that you do not have a say about Russia once you have left the country. When you have left, you have adopted an outsider perspective or mentality according to many. I have been thinking a lot about “us and them” and why having another view makes you not “trustworthy.” It is what propaganda does to you.

I was talking to a Polish friend in Bergen where I am living now. She said that she could only reflect on Polish society and herself once she had lived in Norway after a few years. Sometimes you need distance. I believe a certain distance and self-reflection is what a story-teller needs to have as well. I find it strange that this is not always being valued, and instead it disallows you and your perspectives.

EI: When would you say you started working with art?

PM: It must have been in the last year after my Bachelor in Visual Communication at the Utrecht University of the Arts. For my graduation work for this bachelor, I moved towards trying to figure out all of the shops around me in the streets leading up to where I lived. I wanted to know how the shop owners and people ended up there, many of them were migrants. I wanted to learn what their abilities were and what people did not know about them apart from the street signs outside their stores. Because, for example, in Russia, when I was going back there for a visit, I witnessed that somebody was talking about taxes in the pharmacy and the pharmacist was giving some juridical and tax administrative advice to the client while also selling medicine. This is how I know things to be while growing up seeing my father driving a taxi in the 90s, but he wasn't just a trained taxi driver, he was also a history teacher. He was a drummer. He was a designer.

I was always interested in these hidden stories behind people, in knowledge economies. So the 'behind the facade' project was a kind of alternative yellow pages of my Amsterdam neighborhood. Although I didn't consider it to be art at the time, I now see that it was. You could say my work went from printed matter into film and documentary and later I worked with installation, performance and the live format. Whatever medium I am using, I am always telling stories about people navigating under oppressive structures but also navigating economic pressure by trying to form either communities and subcultures that support each other or being part of shadow economies. These themes are something I have continued working with later in my filmmaking as well.

EI: This makes me think of your film, The Champagne Drinkers from 2015, where you went back to your hometown of Pskov in Russia to record unlicensed taxi drivers from the backseats of their taxis. This film follows the taxi drivers' own personal stories and what they do to survive in financial hardships.

What is it with storytelling that interests you?

PM: The thing with story-telling is that it is also a method to be able to come in contact with people. For example regarding documenting civil disobedience and DIY structures that are built or developed from bottom-up. The interesting thing for me has been to pass forward all these stories and bring them to the front. Champagne Drinkers, was really about these structures that are built by people.

I remember having a discussion about the title of the film with one of my tutors during my master´s at the Sandberg Instituut. They did not think of taxi drivers as champagne drinkers, but rather they were thinking of russian new money, the lavish life and plastic acrylic nails when hearing about the title for the film. But for me the title was referring to this mentality of having to take risks and give up a lot in life. They survive because of this informal economy. Many russian people have been working as unlicensed taxi drivers since the 90s, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when a large part of the population were losing their actual jobs and Russia was transitioning to capitalism. When all the structures really fell after the Soviet union, people had to completely determine their own life and it was not pretty, it also led to this hustle mentality. This is where the title for the film comes from and it refers to a Russian proverb: “One who doesn’t take risks doesn’t drink champagne.” A taxi driver defended their work by citing this proverb.

A big part of my practice was re-telling stories of others and maybe I was looking for a place for my own story to fit in between. Maybe you are seeing your own story assembled in others or that your story is similar to others, and so you share your stories with them. In that sense you want to tell your part of your story through the work. I think that is a trait of someone who is working with storytelling or documentary. Maybe you still try to look for worlds where you could possibly belong.

EI: In what way would you say the theme of the festival, trust, comes through in your sound installation, A Knock From Below Heard At The Bottom, that was presented in the festival exhibition?

PM: This work was not made for this specific festival in Kirkenes, but it was made around a year ago when I started thinking about self-censorship and intergenerational fear. Fear is something that your parents teach you. In one of the conversations in this installation a mother tells her daughter, “Don’t ever tell anything you hear us talk about at home, get it, even walls have ears.” This is passed on in families almost like a cautionary tale that is passed on to generations. I was not afraid of this when growing up in the 90s and spending most of my life in the Netherlands and I was therefore not directly involved in political life in Russia. Of course I read about the opposition leader Boris Nemtsov and several journalists like Anna Politkovskaya being murdered. Then around 2018, people started getting jailed for reposting oppositional content. In the years that followed, opposition leader Aleksej Navalny seemed to succeed in gathering people in both big cities and regions around him, making the idea of a political change seem feasible, which resulted in nationwide protests. I started being more involved but of course, still from the outside, and when Navalnyj was imprisoned and all the repressive laws came into force I started realizing how quick this fear was reactivated in me. With this I understood how fear can be an intergenerational thing. And this project, the assemblage of stories, became an attempt to look for the origins of fear and how intolerance, xenophobia and the cult of force, have led to Russian invasion in Ukraine in 2014 and 2022.

As a migrant, you sort of exist in two realities, which both have lots of stigmas and stereotypes in relation to one another. So in my artistic practice as well as in life, I was concerned with nuancing narratives and creating an understanding of the in-between. For example, I developed a format of assembling film live on stage to allow for multiplicity of narratives by selecting different storylines and accounts with every new performance. But in times of war things do become more black and white. There is no space for ambiguity, and I believe we should be very clear on who and what we support.

I always believed people in Russia operated in spite of and around the oppressive government, which made their accounts trustworthy to me. This war made me realize how susceptible people are to propaganda narratives and how it is much harder, if not impossible, to separate the people from their government. This has changed how I think of my practice as well and I am more careful of whose stories I am including in my work. After the war when Ukraine’s territorial integrity is fully restored, the war criminals are punished and reparations are paid, perhaps there will be space for more nuanced narratives again.

EI: Could you tell me more about the process of selecting your sources of stories that are in your work presented at Barents Spektakel?

PM: Some of the texts are my own reflections and some are gathered sources that are mostly from Russian activists, sociologists, political scientists, independent journalists and social media accounts that I have been following for a longer time. Some of the fragments and sources in the sound installation are referring to the atrocities and violence against the Ukrainian people in the war.

I was interested in finding trustworthy sources and information in an almost algorithmic way, through investigating links between people and organizations. I was archiving these bubble connections that emerged online. In this way, I think I have dealt with the topic of trust by constantly thinking, “can I really trust this information?”.

To me it has been important to state the names of the storytellers in the work description and by stating the names giving it more credibility. I have been watching the military analyst, Ruslan Leviev in his daily analyses with Michael Naki and his words can be listened to in one of the sound fragments in the work. Leviev is the founder of Conflict Intelligence Team, an independent organization investigating actions of particularly Russian troops in Ukraine, Syria and Libya, and documenting war crimes. Both him and Naki are labeled "foreign agents" and have received jail sentences. Naki is occasionally invited to comment on Ukrainian channels. Most people that are part of this sound work do have a criminal record in Russia, and to me this has almost become a proof of authenticity. In Russia, there is a culture of, either you support the government or you are a traitor. Being called a foreign agent today has become the title for everyone who is actively working against the disinformation from the Russian government.

EI: One of the sound fragments in your installation refers to the documentary, I and Others, by Feliks Sobolev, and is an example of a social experiment showing if one test person can trust his own judgment while under pressure from the group's opinion. The group of actors have gotten the task to state that they see two white pyramids on the table in front of them, though it is clear there is one white and one black pyramid on the table. In the end the test person gives in to the group and says that he also sees two white pyramids, though he knows it is not true. Why did you include this scene in your work?

PM: During the first weeks of the invasion in Ukraine, we received all kinds of statistics and survey results about the percentage of the Russian population supposedly supporting the war or not. During this time I heard a talk by the political scientist Ekaterina Schulmann that said that we cannot really trust the telephone polls that are done in an unfree country. She argued that a large percentage refuses to speak at all and breaks the connection, that there are respondents replying they are unsure of their answer, which might be a way to avoid answering the question because they might be afraid of being observed by the state. Then there are the few per cent who answer the phone or even respond favorably to secure themselves or prove themselves to be an extra good citizen for doing so.

Schulmann was also mentioning the problem of how the phrasing of the survey questions were made over the phone that could affect the answers from the respondents. For example, instead of asking, “what do you feel about the special military operation in Ukraine?” (this is what they would officially call it in the beginning of the war), they would say, “the majority of the Russian population is aligning with the position of support for the special military operation in Ukraine, are you aligning with that majority?”. It is how the question was posed that made it easier for the respondent to say “yes” instead of saying “no” and formulate a thesis of their own. This is how I started to think about the documentary by Sobolev and the social experiments that had been made through history. This psychological experiment in the documentary is an answer from USSR colleagues to the experiment in the U.S of Polish-American Solomon Asch in 1951, which tried to show that the Soviet citizen would behave differently, which failed. I started to realize how propaganda and fake news can become a killing machine. Propaganda can turn the world upside down and tell the truth upside down. This experiment shows this so clearly because it is so simple, right? There are two different colors of the pyramids in front of this test person and it is something he can see with his own eyes and yet, other words are coming out of his mouth. This might be an example of several phenomena of how people transform their way of thinking to fit the group or following the leading opinion, so that they can save themselves.

I also want to add that I started working on this art project in the first months of the full scale invasion and I was more optimistic about the real figures from the survey polls in Russia, but now when the propaganda machine in Russia has done its work for a year, you see it starts bearing fruit.

EI: This year’s Barents Spektakel is done. What are you currently working on?

PM: In the coming months, I will have residencies at BEK [ed. note: BEK is Bergen center for electronic art] and at Bergen Kunsthall, where I will explore the scope of storytelling formats in sound, working with live narration, self-developed sound compositions, film scenes fed to a VJ software and improvisational techniques. My next work will most likely deal with the cult of force and the militarisation of our vocabulary, (gender) violence and its impunity. At the same time I’m interested in radio and would love to make a radio opera, possibly borrowing from formats of crime fiction and soap opera. I have a weak spot for soap operas because there is something vernacular about the melodrama and the poor image aesthetics through which they are produced. Having grown up with Latin American telenovelas, they have stayed an inspiration for me. I have been talking with some friends in Mexico about how both crime fiction and soap operas say a lot about the current state of the country they are produced in, and how soap operas can also be used to transmit propaganda or top down narratives to large audiences, while crime fiction was used to package critique on the military dictatorship as entertainment.

Polina Medvedeva was educated at the Sandberg Instituut with a Master in Art and Design. Before moving to Bergen, Norway, she was a resident at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam between 2020 and 2022. Her works have been exhibited at Stedelijk Museum, Al-Ma'mal Foundation for Contemporary Art, WIELS, she has performed at Lofoten International Art Festival, Brighton Festival, and more. Before traveling to Norway and Barents Spektakel, A Knock From Below Heard At The Bottom was exhibited during the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten Open Studios in Amsterdam and at Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris.

Editor's note: Astrid Fadnes, who is part of Hakapik’s editorial team, is employed by Pikene på broen. Fadnes is not involved in the editorial work with texts dealing with Pikene på broen/Barents Spektakel.