MESSAGES FROM FARAWAY

Review of the exhibition Artists’ film international 2020: Language, Tromsø Kunstforening, 15 Januar - 18 April 2021.

Written by Bianca Hisse

What if the communist hammer-and-sickle came from an ancient Chinese ideogram? What if, when we look at a picture of Mars, we are actually looking at the future on Earth? The 2020-version of the Artists’ Film International program, brings up these and other intriguing questions, delving into the speculative and imaginative power of language.

The yearly Artists’ Film International program is an initiative of Whitechapel Gallery in London. This year it features seventeen films collectively curated by various art institutions around the world, from Warsaw to Mumbai to Hong Kong. The selected works are shown throughout the year in the participating venues, and adapted for every context. While travel restrictions are still a reality, the program feels like a rare and refreshing opportunity to have a glimpse of recent artistic works from somewhere else.

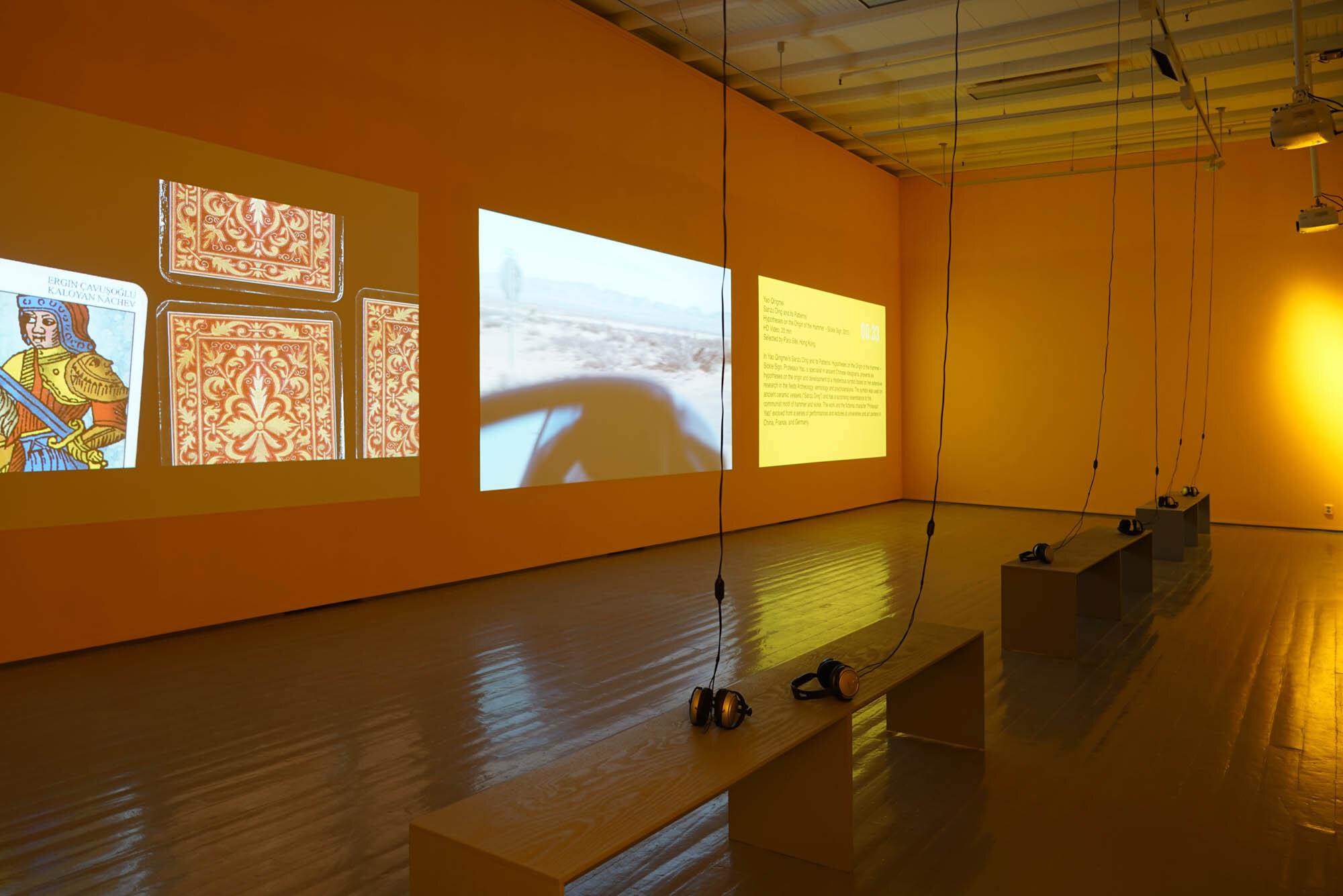

As one can imagine, the selected films could not be more diverse in style. There is, however, a certain democratic uniformity in the way they are presented at Tromsø Kunstforening – six screens of exact same size playing them in looped sequences on bright yellow walls. It reminds me that I am in an exhibition hall and not in a cinema, and I roam around more casually, with my eyes jumping from one screen to the other.

In the first room, a word scrolls down the screen: ‘Clusterrestrial’. There is a strange familiarity in it, which continues in the other words that follow, such as ‘biopixelate’ and ‘abracadastral’ – a sequence of hybrid-looking terms with their explanations in a dictionary style, juxtaposed with clips of nature, textures and details of urban spaces. They belong to the film Passwords for Time Travel (2017) by New Delhi-based Raqs Media Collective. The enigmatic futuristic glossary seems to be merging existing words to conceive a possible language of the future. Some of these new words are not so far from reality, and even seem ironically appropriate for the present time such as ‘legitimagically’, explained as “the manner in which occult legal processes act, requiring us to suspend doubt, disbelief and all effort at comprehension”.

Indeed language, which is the theme for the 2020-program, is a purposefully broad subject and it does not always provide immediate comprehension of things. This is an important aspect in the exhibition and it takes an especially interesting form in Lisa Tan’s My Pictures of You (2017-19). The film is centered around a conversation between the artist and a researcher from the Mars expedition, using NASA photographs of Mars to speculate about a future devoid of life on Earth. As the film goes through various images of desert landscapes, it makes me genuinely question whether what I am looking at is Earth or Mars. A melancholic feeling arises when a song says “home is where the heart is”, while images of lifeless deserted landscapes flicker on the screen. Is this our future home?

In another direction, the viewer travels to the past in Yao Qingmei's Sanzu Ding and its Patterns: Hypotheses on the Origin of the Hammer - Sickle Sign (2013-). In an increasingly absurd and comic series of lectures, the artist performs different characters in an attempt to explain how the Communist hammer-and-sickle has originated from an ancient symbol from the Neolithic period. Both Tan’s and Qingmei’s pieces are gateways to a different time, and language becomes a tool for wild imagination that is also solidly anchored in the real world.

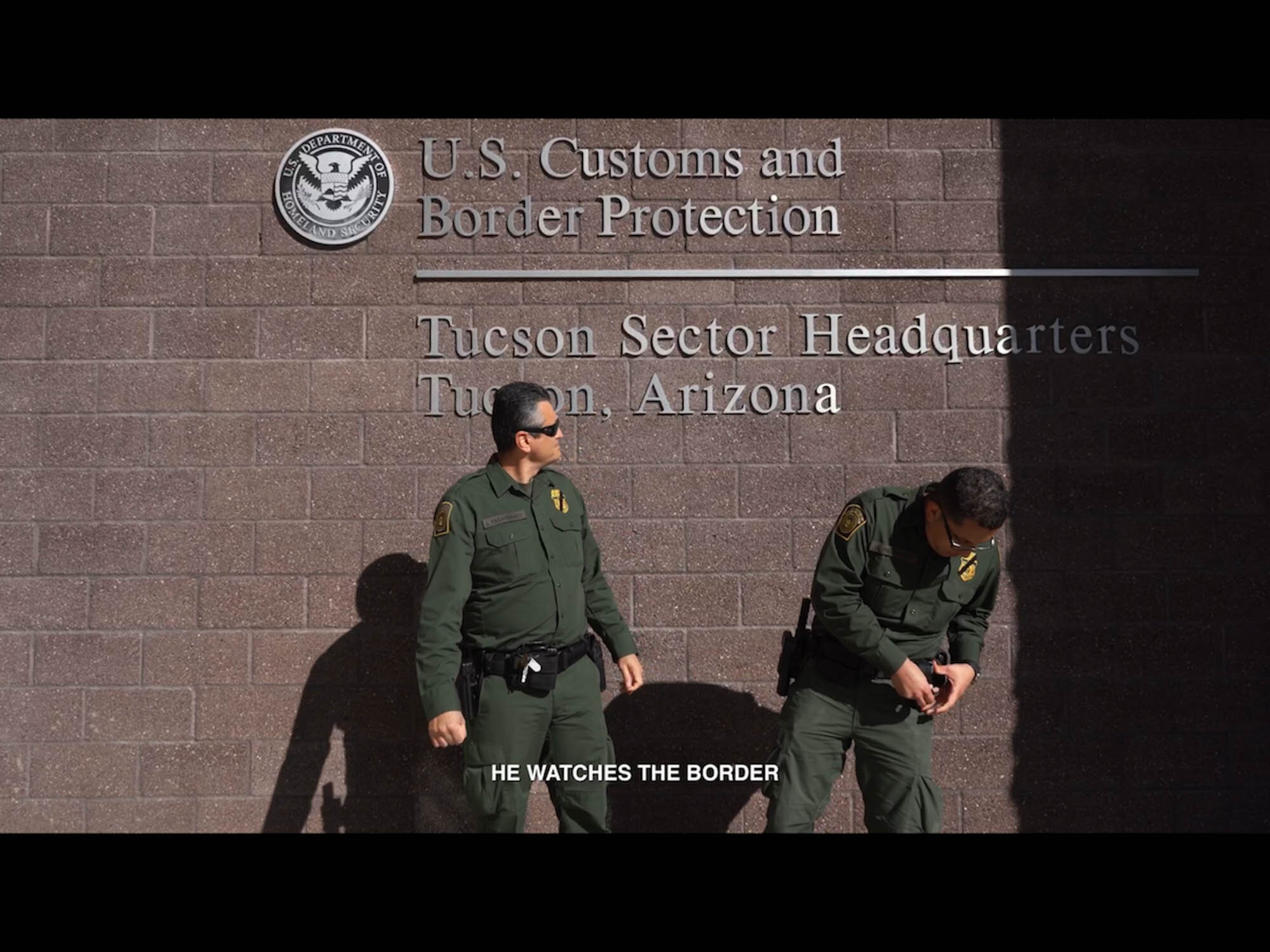

Similarly to My Pictures of You (2017-19), landscapes are also ambiguously evoked in A Grammar of Gates (2019) by Miguel Fernández de Castro. In the work, a monotonous voice narrates sentences from the book ‘A Practical Spanish Grammar for Border Patrol Officers’, eventually overlapping with images from the border between the U.S and Mexico. The sentences refer to a vocabulary charged with control, restriction and authoritarianism. Paradoxically, there is no visible border in the open natural areas shown in the footage. Throughout the film a hand makes notes and highlights words in the grammar book, systematically repeating everything in Spanish with a strong U.S accent. I cannot avoid thinking of myself as a foreigner learning Norwegian and how I quickly memorized key words to read and fill up long immigration forms that come without translation. Taken out of their context, sentences such as “The border is a limit / The border is at the limit” are transformed into poetic statements.

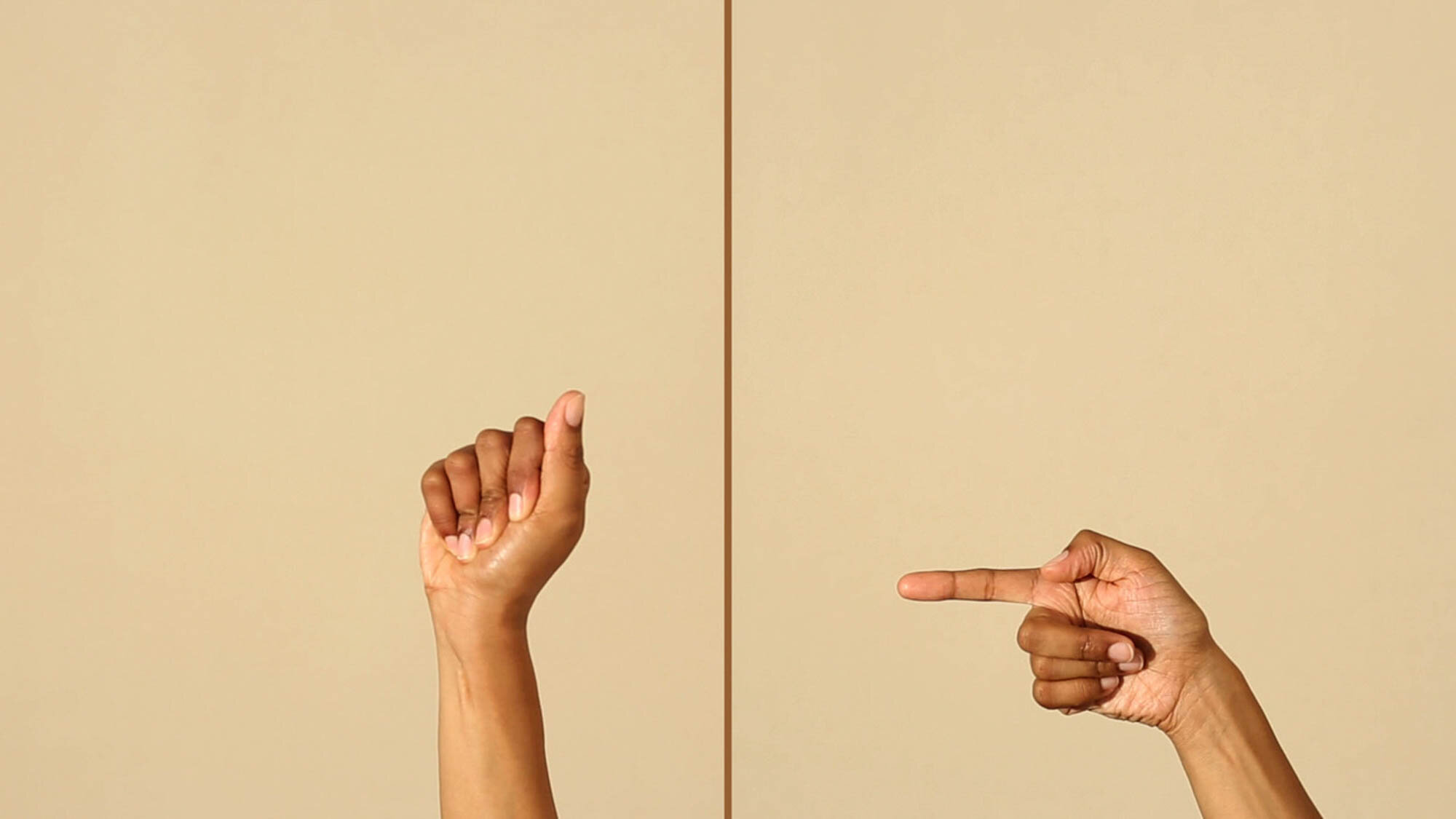

The issue of translation is also nicely raised in Lerato Shadi’s piece Mabogo Dinku (2019). A hand on a plain background moves uninterruptedly and is accompanied by a folk song in a South African language, which comes without translation. While I cannot grasp the spoken words, some hand gestures are recognizable – it pushes something away, it waves, it points to a direction. I immediately refer to Yvonne Rainer’s Hand Movie from 1966 and to the choreographic potential of language. Shadi’s piece reveals how much a gesture can convey without any explanation. Despite our cultural and geographical distances, movement is a universal language, and I do not need a translation to English or any other dominant Western language to relate to the work.

Movement is also a central element in Daisuke Kosugi’s A False Weight (2019). This is the only work that benefits from its own screen in a separate room, which helped me get into the work with more focused attention than the rest of the exhibition. In long static shots, the film follows the daily routine of a man as his body decays due to an illness. In a society where performance and productivity are closely linked, having a highly functional body is an imperative. His aging process happens in front of our eyes and is best illustrated when going to the gym is replaced by visits to a rehabilitation center. His body speaks against his will, in an incomplete language of gaps and limitations.

The variety of narratives presented in this selection of films are not undermined by the thematic frame. From very different and specific geographic contexts to images that are familiar worldwide, the films are as dissimilar as they can be. Still it is not hard to place most of them in relation to global contemporary discourses, giving a comforting impression that we might be actually speaking the same language.