Left in the dark

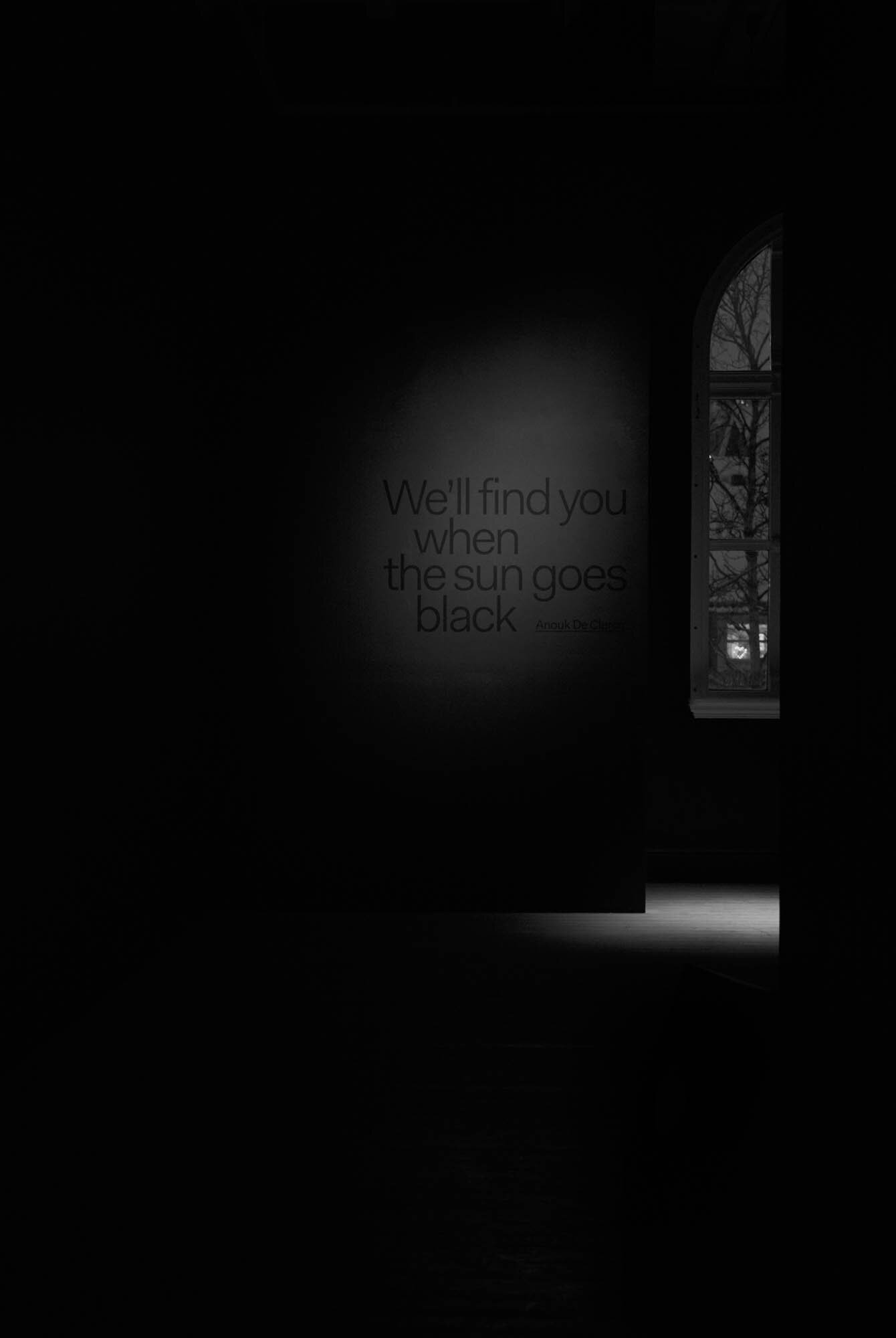

Review of the exhibition We’ll find you when the sun goes black - Anouk de Clercq at Tromsø Kunstforening, part of Tromsø International Film Festival, 17.01.2020 - 29.03.2020 (closed earlier due to the situation concerning Covid19).

Written by Bianca Hisse

During Tromsø's darkest winter period, De Clercq’s films capture the lack of light and suggest the poetics of a new world order. But how can we revise our current paradigms? Can we see something beyond the darkness?

Even though some of Bertolt Brecht’s works were written more than a hundred years ago, he still appears in today’s artistic and cultural production as an enduring inspiration. Perhaps a sign that our struggles are intertwined across generations, or that dark times are are not strictly tied to a single set of problems. The Belgian artist Anouk de Clercq also draws inspiration from Brecht in her videos shown in We’ll find you when the Sun goes Black, an exhibition produced by the Tromsø Kunstforening and presented as part of Tromsø International Film Festival. This is the artist’s first solo show in Northern Europe, and comprises three film works, two of which are new pieces developed after a research trip to Tromsø during the winter of 2019.

ART AND SCIENCE

The exhibition employs darkness both as a theme and as material, delving into parallels between science, art history and the body in a poetic and highly aesthetic manner. For example, the black and white film We’ll find you when the sun goes black (2020) shows us what appears to be a solar eclipse. It is inspired by the ‘terrella’, a magnetised ball used in the past to research the auroras, and by Bertold Brecht’s following poem: «In the dark times will there also be singing? Yes, there will also be singing. About the dark times». In an interesting dialogue between light and darkness, I perceived the work as a reflection on the potential of film itself, pointing to its early beginning when film emerged as a tool to capture and observe the world. The film functions at a good counterbalance to the other two pieces included in the show.

The corridors built between the rooms provided the necessary space to amplify the silence of the piece. They also slightly altered the usual spatial orientation of Tromsø Kunstforening’s second floor, evidencing the well-executed exhibition design made by curator Vsevolod Kovalevskij.

POETICS AND POLITICS

My immediate reaction to the two-channel video installation Helga Humming (2019) was sensory. In the first room, everything vibrated with the immersive soundscape of humming, produced by sound artist Vessel. Combined with the strong aesthetics of the black walls, it was undoubtedly successful in activating a space for contemplation.

The piece is described as a modern take on the world of Bernard van Orley and the polyphonic music of his time. However, before I noticed the soundscape in the room, my attention went to the tall screen where the New York based performance artist, Helga Davis, was posing in a costume reminiscent of the Renaissance. Even though Davis stays almost immobile in the video, and her movement is restricted to the minimal gesture of shifting her gaze from visitor to visitor, her strong presence cuts through the impeccable video work. I particularly connected the work to the notion of oppositional gaze, coined by the feminist theorist bell hooks (Gloria Jean Watkins’s pen name), which is generally defined as a gesture of resistance against the male gaze and white-dominated cinema. The way Davis stands, as well as her clothing, trigger a reference to colonialism. However, as there is no mention to the subject in the exhibition description, I wonder if the connection was intentional or not, especially in a moment when decolonial theories have a substantial space in contemporary art discourses.

As with Helga Humming (2019), I also sensed a strong inclination from the artist to tackle some very important political contemporary issues in the film One (2020). The video shows Davies in an empty dark space, and as the camera slowly moves closer to her, we listen to a performative speech. The text performed by Davis starts with the emblematic «I am not a lone voice, I am many», pronounced by young Pakistani activist Malala Yousafzai during her Nobel Peace Prize speech. The speech develops with sentences such as «we are open», «we are present», «we feel deeply», «we are becoming one». As the text in One continues, it becomes evident that the speaker is definitely not Malala anymore.

Anouk de Clercq’s exhibition incorporates multiple references, some of which belong to strong historical and political backgrounds. Brecht, for example, is a well-known reference broadly associated with Marxism and the orthodox left worldwide. On the other hand, van Orley’s paintings or even the terrella ball convey rather distinct contexts.

DOUBLE DARKNESS

One particular question stayed with me as I walked through the exhibition: why did de Clercq choose to depict a racialized body, through her gaze, and under her authorship? This is a rather complex subject, and I believe de Clercq’s work refuses easy answers. «A body with melanin is always political», the researcher and theater practitioner Deise Nunes told me during a conversation after the opening. This is not necessarily pointing to political content in itself, but to the fact that in all public spheres, the question of who is given space to speak matters as much as what is being said.

New world paradigms can only emerge when our current power structures are uncovered, scrutinized and revised. Several times. As Octavia Butler reminds us, «All struggles are essentially power struggles. Who will rule? Who will lead? Who will define, refine, confine, design?»

At some point, my talk with Nunes came to the notion of Afrofuturism, which she described as ‘a look at Africanity as a paradigm not only of a new political order, but of a new universal order of existence’. Along the same lines, the writer and academic Paul Gilroy idealizes a future without the paradigm of race, while bell hooks affirms that black feminism can finally end to notions of race and gender. I sensed certain similarities with Davis’ performance in One (2020), as she initiates a soundscape of polyphonic voices calling for complexity beyond dualisms.

Instead of presenting us neatly packaged political content, de Clerqc’s thematic frame opens a range of poetic possibilities towards a different future. In the light of our current global situation, the ability to imagine new worlds is deeply needed, and de Clercq’s exhibition We’ll find you when the sun goes black is a an artistic take on a collective desire. While the plurality of references present in the films opens space for diverse readings, I still wish I had left the exhibition with a better understanding of the artist’s position when it comes to the use of all these references. Just as darkness can be a potent territory of invention, it can also absorb subjects in a single tone, making us believe that they are equivalent.