Fluttering Manifestos: When Artists Design Flags

Review of the exhibition Unfolding Questions, Codes and Contours, Tromsø Kunstforening, 10 October – 20 December 2020. Curated by Randi Grov Berger/Entrée

Written by Marion Bouvier

All photos by Tromsø Kunstforening and Entrée.

The exhibition Unfolding Questions, Codes and Contours offers a thoughtful subversion of the official format of the flag, turning it into a support for creativity, political satire and reinvention of symbolism.

The exhibition features 70 flags commissioned between 2012 and 2020 at the initiative of the artist-run gallery Entrée in Bergen. Since then, the flags have been positioned on flagpoles and exhibitions in Bergen, Nesflaten, Stavanger and as part of the Performa Biennal in New York. Since 2015 the Tromsø Kunstforening has been “activating” the flags by exhibiting one every month on the flagpole outside the building.

Flags and nationalism, a complex relationship

Before I first went to see the exhibition, I have to admit that the prospect of writing about an exhibition that was composed entirely of flags posed some challenges to me, due to a complex, mostly unconscious, relationship to flags as one of the embodiments of nationalism. Like every kid in most countries, I learned early on to color in the blue, white and red of the French flag and learnt its historical significance during the French Revolution; yet at the same time, I always felt wary of all the circus around national symbols and the supposed reverence citizens should have towards them.

When I first moved to Norway, I was surprised to discover over time that, although Norwegian nationalism seems rather mild at first glance – definitely not the type of combative allegiance to one’s motherland that I have experienced in the US or China – there is a strong protectiveness around the flag. The same reluctant but deeply ingrained patriotism sometimes comes up unexpectedly in people my age when talking about the Norwegian salmon farming industry, the oil industry (and interestingly, that is also significant for this exhibition), or how progressive Norwegian society is. Don’t worry, we French people are the worst when it comes to passive-aggressive pride, if that can make Norwegians feel better. And back to flags, both Norway and Denmark seem to have a special passion for their national flag. In Norway, there is a law that the flag should not touch the ground, and that it shouldn’t be worn below the waist (bid farewell to your Norwegian flag underwear).

Yet, walking through the exhibition at Tromsø Kunstforening, I felt a strange attraction to the selection of the artists’ flags, but also to their materiality: their soft texture that distorted many of the pictures, the ebb and flow of the fabric and the desire to unfold them to see them better. The exhibition layout is purposefully austere, with all the flags aligned in rows at the exact same height from room to room. The white walls, the silence and stillness are only occasionally disturbed by a slight flutter of one of the flags as I pass them. This eerie atmosphere contrasts with the playfulness of many of the flags, which range from purely aesthetical creations to political statements. This great diversity of topics, colors and images is paradoxically highlighted by the uniformity of the medium.

Political explorations on flowing fabric

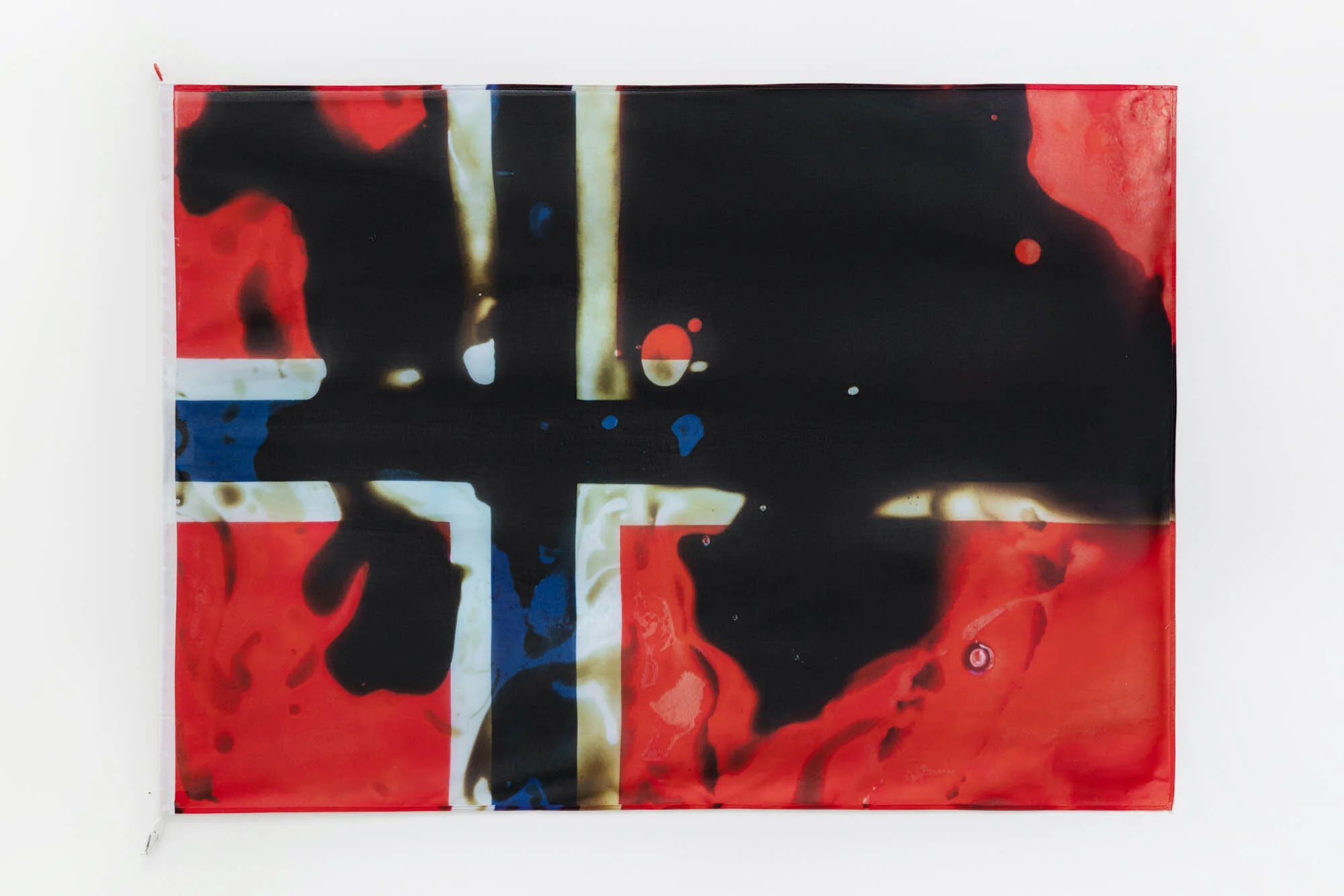

Flags are historically political, and to see them reappropriated by artists felt very refreshing. It also hints at how political art is or can be. That was shown quite vividly when Oliver Ressler’s Oil Spill Flag (2020), which is artistically speaking far from the most remarkable, became a subject of controversy in Tromsø: it ended up being stolen by a retired supreme court attorney (!), before being grudgingly returned by the thief after it had been reported to the police. I doubt that this would have happened if the “offensive” picture had been a framed photo within a gallery; but I am guessing that what was so offending to some was to see the flag of Norway floating high in the sky of Tromsø with an oil stain on it. It blurs the boundary between art and reality by using the flag in its original function, and it turns the symbol of pride into a symbol of shame: the pollution and destruction of the “untouched” nature that the state has built so much of its new nationalism on.

Even more interesting, in my opinion, is Joar Nango’s The Sámi flag hand-drawn from memory by a white, middle-aged man (2020), which is very much what its tittle describes: a reproduction of a hand-drawn, crayon-colored drawing of a Sámi flag. The shapes are correct enough to be recognizable, but the colors wrong enough to make a statement. In the current context of racist outbursts (see the recent case in Tromsø of a young woman speaking Sámi receiving insults from an older white woman), Nango’s work reminds us that there is still considerable ignorance in Norway towards its own first-nation people. There is also a lot of humor in the choice of the descriptive title and the childlike image when printed on such a large and formal medium.

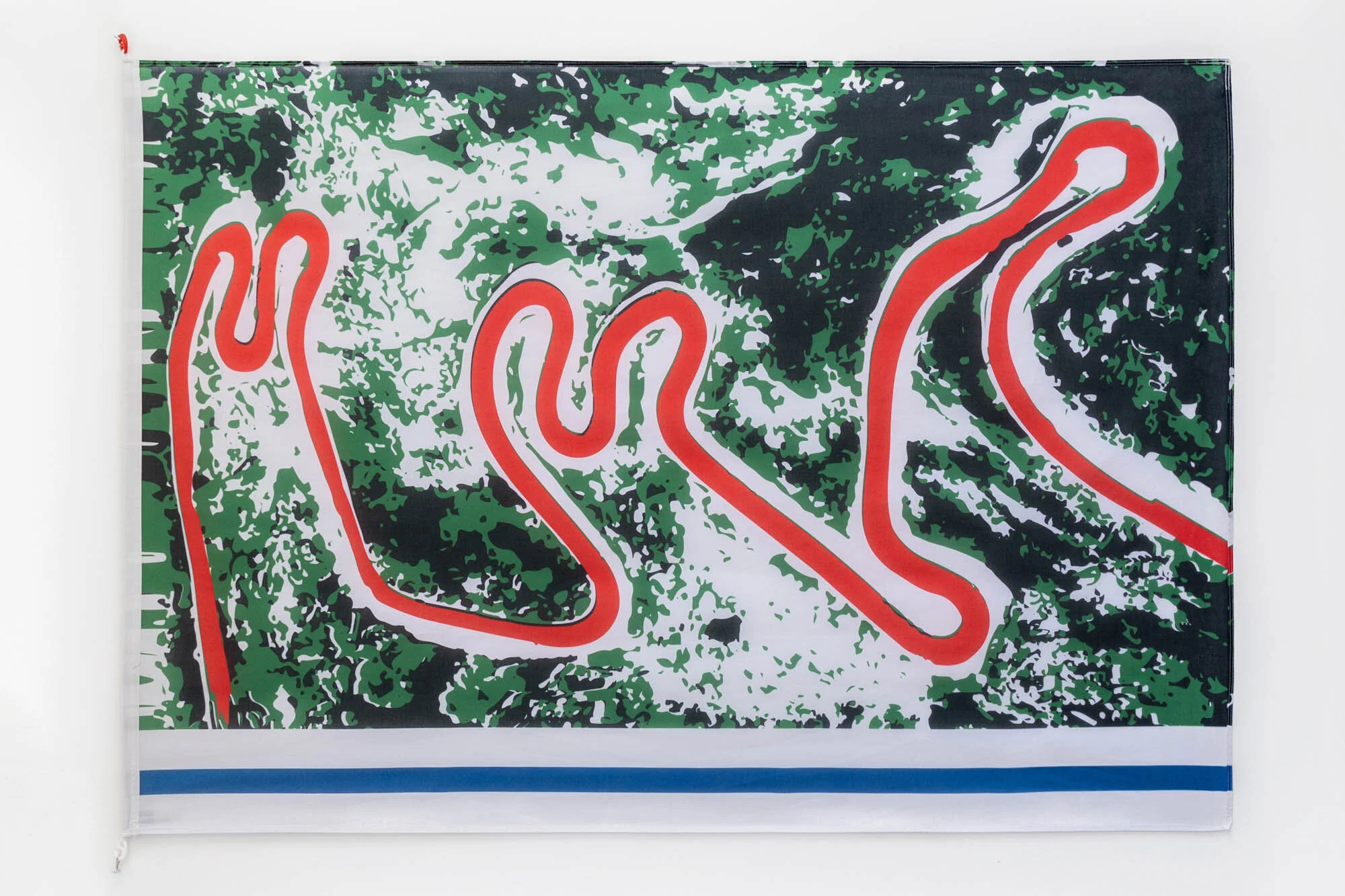

There is also Jordan Nassar’s A White Bird Over Your Heads (2019), which felt even more topical in the year 2020. His flag looks abstract at first glance, with a meandering line traced in the midst of a greenish landscape. In fact, the flag depicts the road between Nablus and Jericho in Palestine, and comments on how the Israeli occupation is so twisted as to even complicate the course of roads: this winding journey takes 2 hours and often more for drivers with Palestinian car plates, while there is only around 40 km between the two cities as the crow flies. The artist says he wanted “to call attention to the freedom of movement,” and the lack thereof that Palestinians experience. For us in Europe who indeed took this freedom for granted, the pandemic was but a small glimpse into what territories under occupation go through indefinitely.

In Andrea Spreafico’s Nor (2012), the political transgression is much more subtle – and didn’t cause any stir. The Italian artist living in Bergen has swapped the blue of the Norwegian flag’s Nordic cross with the green color of his homeland’s flag. He blends the two flags like I imagine his belonging to the two nations can overlap, thereby creating his own emotional territory.

Symbols of imagined communities

If the flag format inspired direct political considerations to many artists, others clearly played with the required medium in poetic ways, to comment on the human experience, or to interrogate language through symbols. Sjur Eide Aas’s I miss you the most when…looking up at the night sky (2020) made the stiff flag pole suddenly less intimidating, and brought forth a melancholic mood to the flag. I immediately liked the flag, and found the artist’s statement even more interesting, as he directly addresses his forego to the political associations of the flag, as he writes in the description “If a place is just a moment in time, so a flag I believe isn’t really anything at all "(…) And in time it will pass, as all things do.”

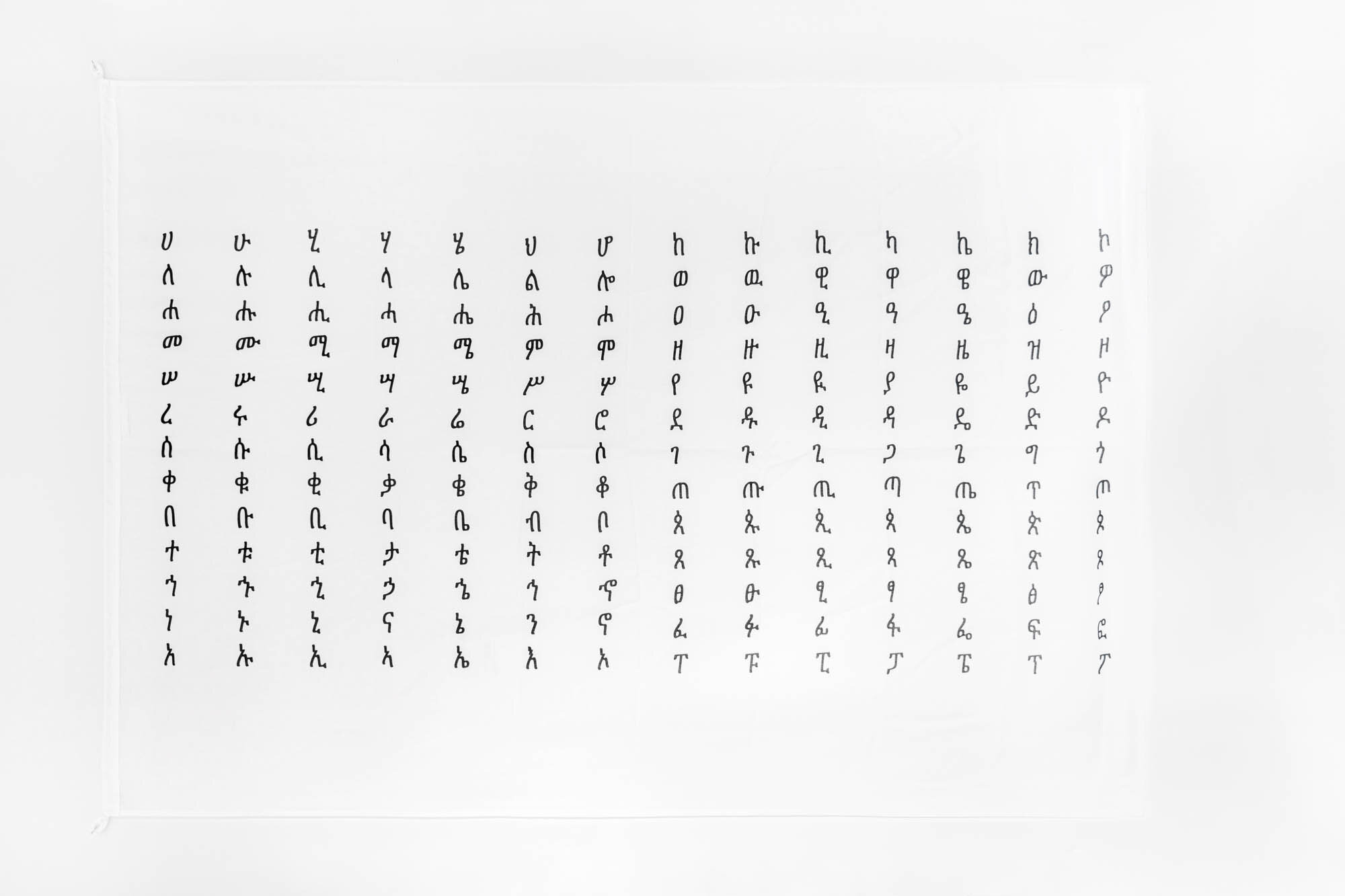

The works of Magnhild Øen Nordahl and her Dit (2012) flag, Wendimagegn Belete’s Fidäl (2020) and Toril Johannessen’s UNSEE (2013) have in common to embrace the traditional symbolism of flags to question language and societies’ accepted symbols as formal means of communication. Like Øen Nordahl who blurs the clarity of the arrow as a widely-accepted symbol, by placing it on a flag, bound to float, shift, and change direction with the wind.

I found myself greatly enjoying the exhibition Unfolding Questions, Codes and Contours as it is a rich exhibition that invites the viewer to see beyond the form, and to question its own gaze on symbolism and nationalism. The sheer number of flags and diversity of artistic expressions make it remarkable and, in some ways, can be compared to going through a theme park of miniature buildings of the world – only with artists offering us an alternative, and in many ways more inclusive, world view.