Mechanical Poetry

Interview with visual artist Lawrence Malstaf, Tromsø, 2020

Written by Mihály Stefanovicz

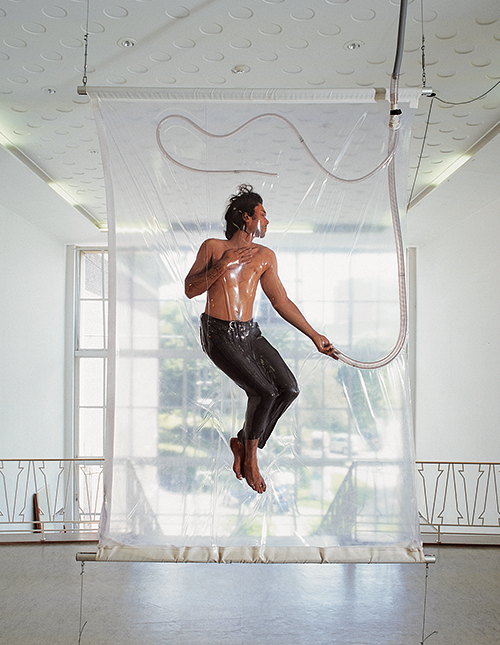

Lawrence Malstaf (b. 1972, Bruges, Belgium) is a visual artist renown for his kinetic works and large scale mobile environments. His practice represents the synthesis of installation art and theater stage design with a focus on, as he himself describes it, «movement, coincidence order and chaos, and immersive sensorial rooms…»

How did you end up in Tromsø?

My wife, Liv Hanne [Haugen] is from Tromsø. She is a dancer. At the time we met she used to work for a Belgian choreographer in Brussels and I happened to be the scenographer for a piece. We lived there for ten years. Both our son and daughter were born there. We decided to move to her hometown when they were starting school. Living in Brussels with two small children was not ideal for us. Here [in Tromsø] the centre of society seems likelier to be family and children, while in Brussels it is work and career.

You don't regret this decision, do you?

Not at all. We do not plan to move back, although it forces me to travel frequently. I have been facing this dilemma for a long time: I am willing to show my work worldwide and at the same time I am aware – and trying to be critical of – environmental issues. It is a bad combination. Most of my works are quite complex, and therefore technically demanding to assemble. Currently I am looking into solutions, such as video manuals, smart glasses and other ways of remote assistance in order to be able to build up my shows without having to travel.

I have been living here for ten years, and quite naturally, I’ve also been observing my surroundings. People often ask me how the surroundings influence my practice, which isn't clear at all. Anyhow, lately I experienced a naive awakening…

There, you see…

[He points to the corner where a large pile of dried Tromsø Palm is gathered in a tarp]

I finally started to discover the abundant natural materials in my close proximity. Later on I might combine them with motors and other electronics, for that is the usual flow of my work. Besides, I have another idea about designing some sort of a game, a set of rules so to speak. I would apply these rules to make a construction, for example, of Tromsø Palms. While if I sent the work (set of rules) to another location, I would only transport the minor elements, or even just the instruction containing the 'Rules of the Game' and suggest that the Tromsø Palm is substituted with an equally common local material of similar characteristics. This is another solution for reducing transport and travel.

You are trained as an industrial designer. According to common comprehension, art academies are the side roads leading to the art world. How did you personally find your way into it?

Perhaps I was preparing to be an artist far in advance of my education. Of course I was considering to go to art school, but at that time everybody in my – close and far – surroundings were keen to direct me towards a more functional field such as architecture. I attended the open day at the Architecture school in Antwerp which was together with the art school. Then, by accident, I come across this field, still unknown to me, which was industrial design. When I saw the models, the material research they were working on, it struck me as a highly creative field.

Of course, later on while completing the program, at times I felt frustrated. Especially during the year we were focusing on consumer products. It felt like we were meant to artificially invent new needs for the consumer. Anyways, it turned out to be a creative study which introduced me to the newest materials and to contemporary solutions that we actually deal with in everyday life. On the other hand, at the Antwerp art academy, at least in those days, it seemed to me as if they were primary using a more traditional approach: working with clay, plaster and with steel at the most...Maybe this is only the way I remember it in order to convince myself I made the right choice.

If I tried to put you in a the tight box of kinetic sculpture, would you accept that?

Sure, on Instagram I often use #kineticart, [he laughs]. To me kinetic art also has a bad connotation: There is a certain spectrum that focuses tightly on robotics and overlooks everything else but the technical side. I obviously do like robots and motors, it's evident from my work, but not for their own sake. There should be enough poetry involved in order to shift the focus beyond technology.

Do you relate to Theo Jansen for instance?

I definitely do. I have never seen his work live sadly enough.

It's fascinating you know, he seems to belong to a certain type, along with Richard Serra for instance: They have a singular vision which they develop until the very end where it becomes...something evolved, refined and thoroughly thought through. I don't work this way, although I do repeat some elements from one work to another, yet each project tend to be quite different. Sometimes I find myself slightly frustrated at the beginning of a new process when I am learning something over again.

[He looks to the right, at a new piece under construction as he continues]

I am already aware of a number of details that I could improve on this work if I decided to make a second one, and it is not even ready yet. If we pick Shrink as an other example, it could evolve further in term of dimensions and of the number of people it infolds...etc. But I choose not to go that way.

I can’t help noticing that air plays a crucial part in many of your works. As if you attempt, in several ways, to make this otherwise invisible element apparent. Would you call air one of your mediums ?

I am primarily interested in unpredictability. I often turn to automatons, to machines that repeat certain patterns and motions in an unpredictable way. Air is a medium that is quite unstable which allows for variations to appear. In Nemo Observatorium, for instance, when the styrofoam particles are blown around, the spectator attempts to recognize repetitive patterns, in order to find some kind of system in it, but, naturally, it is not possible. In short if you are working around themes such as repetition and unpredictability, air is an evident and easy medium to activate.

Several of your projects are quite monumental, as they're designed to appear on theater stage thus they are meant to fulfill a grandiose space. Others appear in a central position. This made me think of the term ‘spectacle’, as of striking and arge scale. Is this something you have considered?

There is a delicate, thin line between spectacle and spectacular. The most crucial aspect is the context: Sometimes I get calls from rock festivals that wants to put Shrink on stage, and I have been contacted by commercial productions as well. I imagine it could work in those contexts too, and people might even be amused, but that is exactly where it falls into the category of ‘spectacular’. As I have said, the context and the intention of the presentation is what makes the difference. If I allowed twenty people at once into the Nemo Observatorium it would instantly turn into somewhat of a party, while with one spectator at a time it stays quite focused and something rather meditative.

Dominantly you set two entirely different scenarios: At one hand there is the one to one experience, while at the other hand there is the classical theater set, in which a larger audience is facing the work.

The individual viewing of the work is definitely much easier. Think about allowing a single person into a black box: In a darkened space you just light a match and the person goes 'Woooow'. That simple experience itself might be breathtaking.

It allows the artist a lot more control over the situation. Many of my older works are designed in this fashion. Gradually I am moving into another direction where several people activate the work simultaneously. It is intriguing to observe how people take upon the role to perform for each other. This experience opens up the very social dimension which the individualized works lack.

How far have you gone in terms of commercial context? When I saw Shrink the first time I was reminded of the dutch fashion designer Iris van Herpen. Sometimes her work is associated with fetish.

She actually invited me to collaborate on a fashion show. It took place in Paris, with three Shrinks installed in the middle of the cat walk. The models vacuumed inside were wearing her clothing. That was perhaps the most spectacular context I have ever agreed to. In my opinion her design is truly outstanding, but it still is situated within fashion, which is a very tough, commercially orientated environment. This was the first and maybe my last encounter with the fashion world.

Anyhow, I do not aim to strictly separate one context from another, but rather try to shift fluidly between them. I work a lot as a scenographer for theater productions. Some of my projects started as solely scenography. Later on they transformed into another, more autonomous format for exhibitions. While I am designing scenography I tempt to simultaneously envision an exhibition. This very interaction between the two fields, I believe, is the reason why I often come up with a spatial design or a larger object where people are invited to be participants instead of passive spectators.

Is there a non plus ultra for you, some long desired point of arrival?

MoMA, Turbine Hall...[he laughs]...You know it's all the cliches that you can imagine. Any of the top venues would be great to show my work at, but I don't feel unhappy because it hasn't came through yet. Right now I am making some new works and design for Perspektivet Museum. It is admittedly a small, down to earth place in comparison to the previously mentioned ones. You might assume it isn't anything glamorous, but it is not about that. Rather it’s about the people you work with. The project we are working on is about Sara Fabricius, known as Cora Sandel as an author. She is an early to mid 20th century Norwegian female writer and painter. Perhaps not the most familiar name unless you are really into Norwegian literature. Nonetheless she is very significant. This is going to be the first, if I may say, proper exhibition about her work. Perspektivet Museum is involved in the process wholeheartedly: We travelled to Paris together, thereafter went to Bretagne where she used to live for a period of time. Furthermore I have a whole lot of freedom throughout the entire process. I get to execute new pieces which I have a chance to also show elsewhere.

As I said it isn't MoMa in any sense, but I must say that artistically it is very rewarding. Keep in mind that at top venues you must consider a great number of details that doesn't even directly relate to the work you want show. It obviously comes with huge expectations and with equally big responsibility...you need to be able to handle all of it if you are panning to exhibit at such places.

A more important ambition is about matter and energy. My ultimate project would be creating an experience that besides being magical and enlightening would also be ecologically balanced. I know it might not sound special, but we have such a long way to go. Just try to make something as brilliant as a Tromsø Palme, that grows two meters in one year, gets all its energy from sunlight and decomposes into fertile earth when the project is over.

The possibilities in physical and imaginary reality are infinite. Artists like scientists have the luxury to take time, to observe, then interpret, frame and represent.

Currently Lawrence Malstaf is also developing a new project with the artistic collective STATEX that he is part of together with Liv Hanne Haugen, Tale Næss, Amund Sjølie Sveen and Jon Tombre. STATEX produces happenings and performances and have been invited by KORO, Raumlaborberlin and Tromsø Kommune to take part in the ongoing project Tromsø Waterfront Lab (2020-). In this new project, the Tromsø Palm again plays an significant role and after our conversation Malstaf shared with me a quote used by STATEX that relates to his thought on matter and energy.

“The first law of Thermodynamics says:

Energy can never arise or disappear.

Sunlight becomes a tree, trees become oil, oil becomes plastic.

Plastic washes up on a shore and is burnt into CO2 and heat, CO2 becomes a tree.

Nothing gets lost

Matter is energy that transforms endlessly, in various states.

All matter - everything that ever will exist in the future- exists already.

The second law of Termodonamics says:Complexity in a system always increases.

A handfull of broken glass can never fall to the ground and land as a wine glass.

The future cannot be simpler than the present.

Planet earth is formed, lightning strikes and organic life arises.

Homo Sapiens makes machines with artificial intelligence and manipulates its genes.

All change is irreversible

We can never never go back to how it was before.”