HC Gilje on exploring unknown landscapes

Interview with HC Gilje, november 2022.

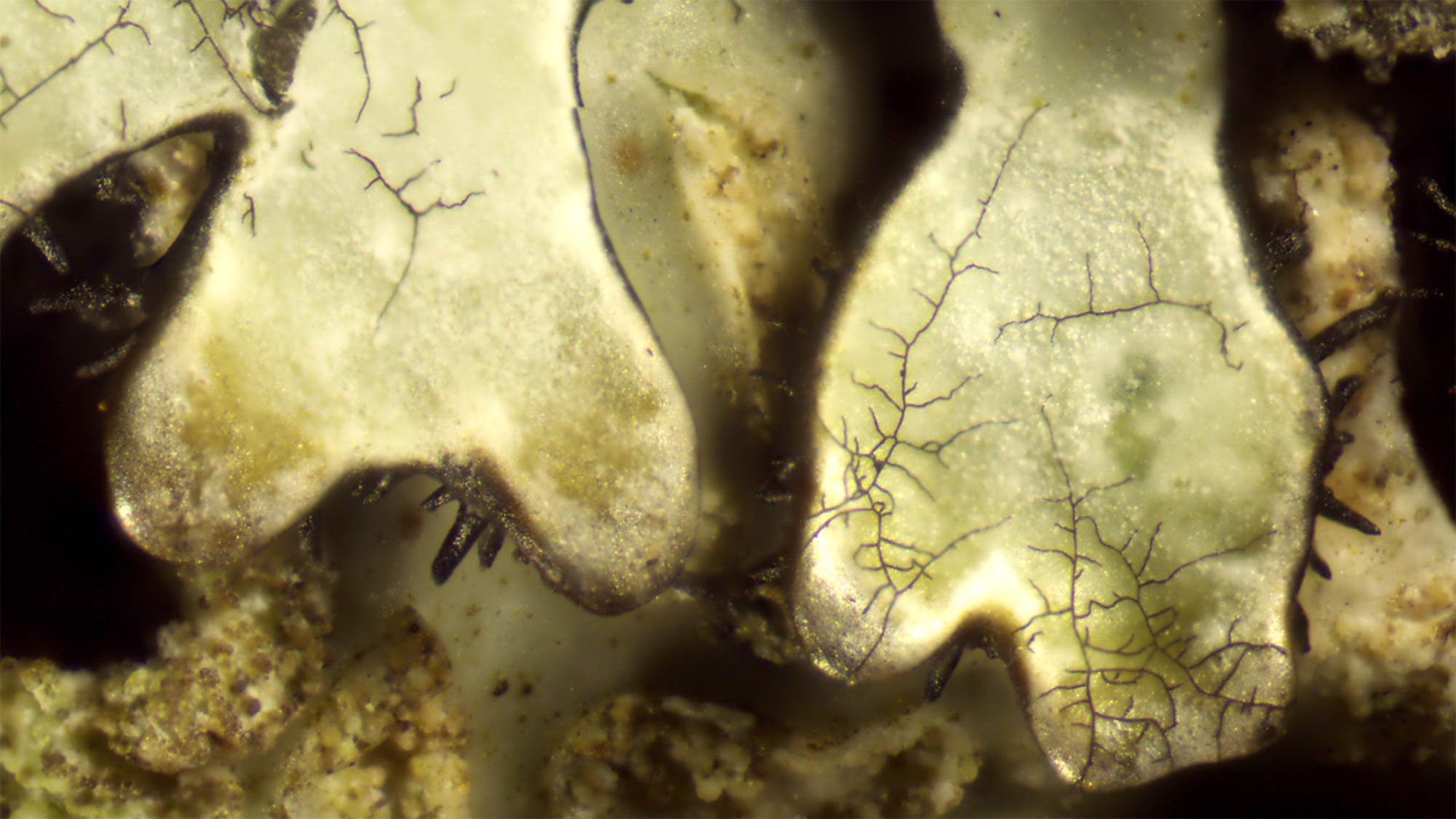

Between the 13th and 16th October this year, HC Gilje presented four recent film pieces at the Arctic Moving Image & Film Festival 2022 in Harstad, as well as a new commissioned work. In this new work, a film entitled The intimacy of strangers, he used a microscope to explore the “depths” of a lichen found on a stone fence, marking the perimeter of Trondenes Church in Harstad. We discuss this newly commissioned work and how it fits into Gilje's wider practice – which he himself describes as an installation artist making “conversations with spaces”.

Written by James S. Lee.

Hello HC! Can you tell those reading this a little bit about your background in the art scene and how you started getting into film?

– I started out doing experimental video before going to the art academy in Trondheim in the late 90s. In the early 2000s, I was involved in what was called the “live cinema” scene. We twisted the idea of adding visuals to concerts, as we invited musicians to do soundtracks for our improvised cinema. It was nice for a while until Ableton Live (Digital Audio Workstation software, used to edit and compose live audio) came around and people had fancy finished video clips they played back with the music, and this scene died a little bit.

– We were into free jazz improvisation and players responding to each other. I wanted to replace the human player, and that was something I took with me into my project “Conversation with spaces”. I wanted to replace human players with the environment I was doing my work in. So that was the starting point: to move my studio to the places I was making work in, to have a dialogue with my surroundings. Small transformations using sound, video or light, something that did not physically transform the space, but adding another layer, or hiding something that was there.

– I do not know if you have read Gumbrecht but he talks about the intensification of the experience, and I am trying to get this feeling when, for example, often at a good concert or something where you really get into it without having to understand it, that it becomes part of you, somehow. He describes it as being “lost in focused intensity”. I think this is a challenge to do in contemporary art these days, as it is quite intellectualised, which removes this option a little bit. But that has been my path.

– I am also quite into this idea of making tools as a way of interacting with my surroundings. Again, we were thinking (when we were doing these live video improvisations) of software patches as instruments, that we should know them well enough to improvise with them – but also build our own instruments for whatever needs we had. Ursula Le Guin, has a nice way of saying that technology is the “active interface” we have with this world. Even clothing, for example, is a form of technology. For us now, it is impossible to interact with the world without using some sort of technology!

I would like to move onto this specific project in Harstad. Maybe you could give me a little background. Why did the invitation appeal to you?

– I had known about the festival for quite a few years, as Helene Hokland (festival director and founder) had approached me to show a work already in 2016, but it did not work out then. So I have been wanting to do something from that point. I like how they frame the festival as both a “moving image” and “film” festival. Another really important thing was that this festival came with a commission; I did not have to apply for extra money to realise the film; there was a production budget to actually make the film, which is something underrated that artists really appreciate.

– We went to look at a lot of locations, and chose Trondenes Church in Harstad which happened to be the same location as for Hanan Benammars performance last year (This is our body). It is the nicest walk in Harstad, from the city to the church, but it was also partly because I was blown away by the place, the human history, the Soviet prisoner camp in the war, and of course the lichen.

Can you talk a little about the commissioned film itself and the end result?

– I have done quite a lot of projects with microscopes before, and, in particular, together with Justin Bennett ( sound artist and frequent collaborator). We did the live improv project mikro as part of Dark Ecology (a three year project curated by Hilde Methi and Sonic Acts) in Kirkenes in 2016. We collected objects from a closed down mine, a mine located practically in the centre of Kirkenes. I had a microscope capturing textures of the various objects and creating very much a “flicker film” aesthetic, while Justin worked on the soundtrack, utilising the objects we collected.

– In the film rift (2016) (commissioned by Dark Ecology) I worked with animated microscope images of plastic wrappings (packaging) for consumables and to think about plastic, and also at the same time, linking it to my hero Len Lye. He was one of the first experimental filmmakers who painted and scratched directly on film already in the late 20's, and he was different from other avant garde filmmakers as he often sampled from old jazz records or from world music. His films always had a kind of groovy soundtrack, which I really appreciate.

– After working on rift, it made me want to do something more organic – to follow the structure of something like a leaf, so you could think of it as a landscape. So, since I made that film in 2016, with the plastic, I have been wanting to make a new set-up where I can work this way, and to work with depth. So that process has been churning for many years. And I started making prototypes maybe a year ago. I had also been reading Entangled Life (2020), a book about fungi by Merlin Sheldrake and Underland (2019) by Robert MacFarlane. This got me thinking about the fungal life all around us. So my work with the microscope animation platform and my interest in fungi came together for this project.

What were you thinking about when making The intimacy of strangers? What was the process like?

– It was about the idea of exploring an unknown landscape, a bit like landing on a planet and exploring it with a Mars probe, because lichen is an alien landscape living next to us that we walk by without noticing it.

– There is a piece that I really like by Michael Snow, La Région Centrale (1970), where he had flown in a 16mm camera mounted on a huge rig onto a mountain. This camera could move in all directions. It looked like a probe that had landed on an alien planet and the soundtrack, because this was in the 70’s, used sound signals to control the motion of the camera. But he also uses those sound signals for the soundtrack, so it's really, really weird. It starts out in these pretty straight motions, and then suddenly it spins around, it's really wild, especially if you see it on a big screen. I really like this idea of going somewhere and treating it as a new place that nobody has been, that was my angle.

If I had not been told it was lichen, I would assume it was digitally generated. Did the end result surprise you?

– In my previous microscope works I have often worked with unspectacular objects that turn into unexpected textures under the microscope. With the lichen it was different since they are already interesting to look at with the bare eye. What surprised me was the extreme variation of the lichen on just one rock.

I was wanting to reflect on something I noticed about your recent work where you are stressing the importance of non-human entities. Where does a collaboration begin and end? Is it a collaboration with the lichen and the people who build the wall that the lichen found a home upon?

–This film would not have happened if the fence nor the lichen were there, and having grown for 100's of years. So in that way it is a collaboration. I do not know when my interest in this started. Alva Noë, an American philosopher (in the generation of new phenomenologists) writes about vision as an “active” act, that you don't get the world in through your eyes as images, and is, therefore, more like touching. He writes beautifully about how your perceptual apparatus is so different, if you are a human or an octopus or whatever.

– I am interested in how we are in the world, but the world is also inside of us, in so many ways, in terms of what we breathe, eat and drink. It is ironic that the shit we put into the world ends up inside us anyway! If you start to think of all the cells in our body that don't contain our own DNA, I find that mind blowing. I think it’s strange that this is not brought up more. It is so fascinating how boring we make the world!

– Another way of thinking about our relation to the world comes from the Russian scientist and philosopher, Bogdanov (a contemporary of Lenin). Knausgaard writes about him in his latest book, how Bogdanov views science as empirical, as something that we use to look from the outside into something else, but he claims the only thing you can find out through science is the limitations of our own human gaze and human mind. This means I can never learn what it is to be a lichen, but I can see what they look like at a microscale.

Do you feel limited by the cinema format?

– There were three pieces I showed at the cinema at Harstad that were less obvious to show there not because of the space, but because there is no beginning nor end to these films, they are designed to keep going, as they were designed for an exhibition space. That is something I find quite challenging. The film Barents (mare incognitum) is primarily shown as an installation. But on the other hand I really like the space of the cinema. It is great when you're in a proper cinema, where it is a communal experience, and it becomes a “conversation with the space”!