A Delicate Balance of Terror

Review of the Film Concert: Burial, part of Tromsø International Film Festival 2023 (TiFF). A Film by Emilija Škarnulytė, with live music by Timo Kaukolampi, Driv, 18.01.2023, Tromsø.

The film Burial, as presented at TiFF 2023, demonstrated an impressive first foray into feature length territory for Emilija Škarnulytė. The film blends well executed overhead drone work, long panning shots, and Škarnulytė’s signature mermaid motif – all in, it seems, an effort to capture the incomprehensible sublime of nuclear fission.

By James Lee

Since graduating from the Tromsø Academy of Contemporary Art (now Tromsø Academy of Fine Arts) in 2013, Emilija Škarnulytė has moved up to “the big leagues”. She has been curated into programming at MoMA, New York (2022) and at Tate Modern, London (2021), as well as having won the $100,000 Future Generation Art Prize. For this “homecoming” of sorts, Škarnulytė showcased her latest film Burial (2022). The 60 minute documentary got the full on cinema-concert treatment, with an accompanying live score from musician and composer Timo Kaukolampi.

A Suspenseful Atmosphere

The film itself consists primarily of footage from inside the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant (INPP) in Škarnulytė’s native Lithuania – a plant currently in the process of being decommissioned, with its spent nuclear fuel being “buried”. The plant is the sister-plant to the infamous Chernobyl plant in Ukraine, the film will go on to inform us.

The film concert starts when Kaukolampi brings in touches of bass, heavy and disconcerting electronic music. He is creating a suspenseful atmosphere in the Driv concert hall. As the film starts to play it immediately wants us to feel the scale of the power plant; one shot in particular near the start of the film shows the enormity of the power plant, contrasting these human workers, their tiny bodies, against the cavernous backdrop of the interior of the building.

The narrative device (white text appearing on the screen from time to time) explains that Lithuania, to accede to the EU, agreed to the decommissioning of this nuclear power plant (such were the fears at that time, due to the similarities between its design and the design of the Chernobyl plant).

Capturing the Sublime – not the Political Nuances

I don't think in any way this film can be interpreted as a pro-nuclear film, but to what extent this film is an anti-nuclear film is definitely a question that remains long after. If it was not for Škarnulytė mentioning before the screening that her grandmother's blindness was in all probability caused by radiation as a result of the reactor meltdown at Chernobyl, one could watch this film and not really feel that it wants to take a stance on the issue of nuclear power one way or another. The politics of nuclear power – whether power plants should be built, or whether some nuclear power plants should be decommissioned – remains unengaged.

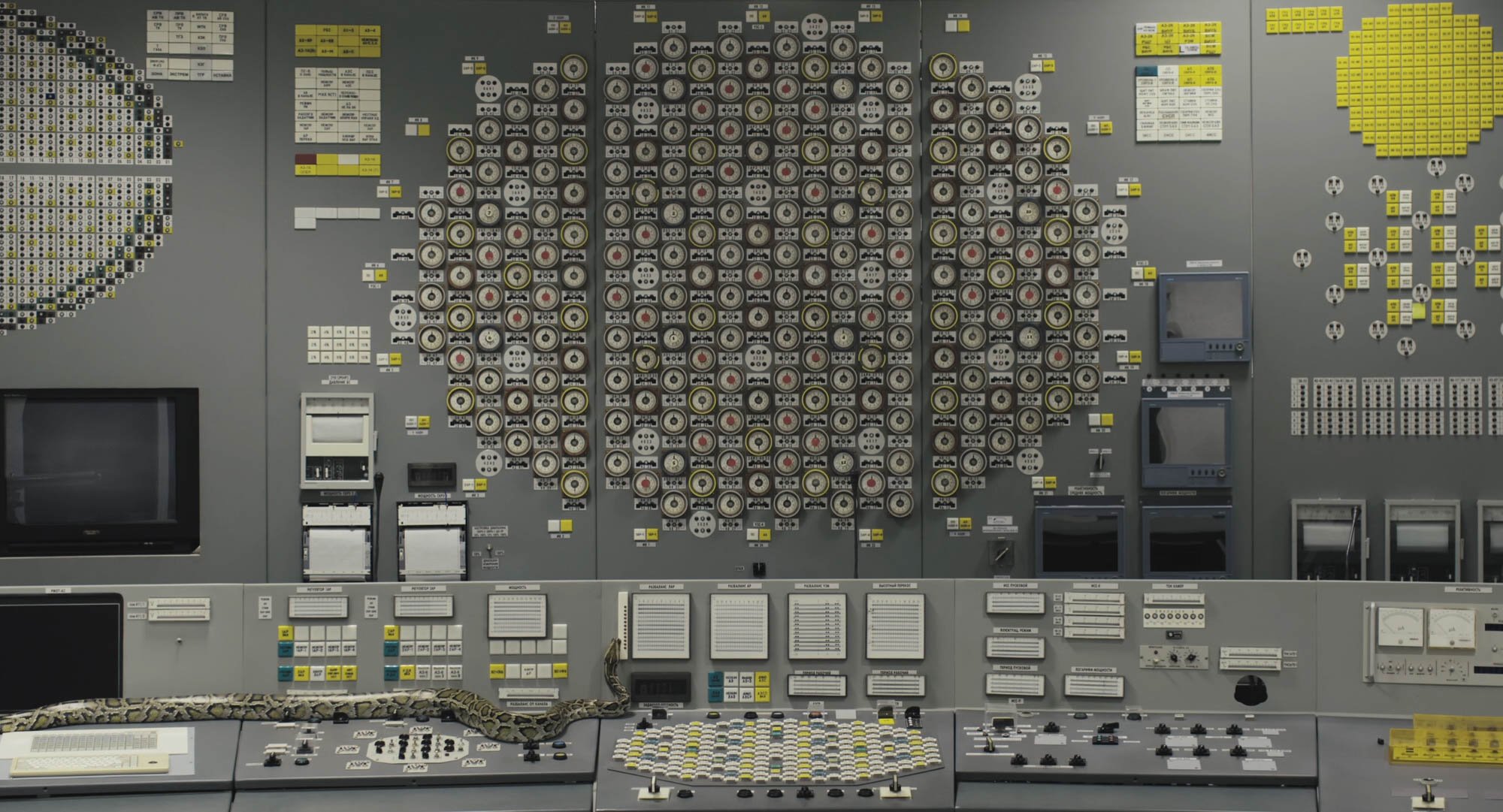

If one can bring in the classic aesthetic theory from Immanuel Kant, one could say the film is an attempt at capturing the sublime; that it is interested in conveying the terror, the awesomeness, the magnitude of nuclear fission. Burial, with its long, long pans that seem to go on forever, attempts to capture the scale and incomprehensibility of all the processes that are needed to make this system of energy production work. These cinematic techniques try to convey the sublime of the hundreds of thousands of years of nuclear waste remaining dangerous; the sublime of the complexity of the vaults this waste is to be deposited into; the sublime of the size of the nuclear plant itself; the sublime of the total number of buttons on a console.

The soundtrack on the night by Kaukolampi is definitely in tune with this attempt to convey the sublime. It terrorises and it feels big with its ever present low end frequencies; pulse-like and often coupled kick drum patterns build tension and convey a sense of forward momentum, particularly pleasing when the camera itself is moving – often panning – towards something, adding a sense of unease as to what will appear at the end of the pan.

This live scoring, despite often being highly engaging, was on the night, however, often a bit too much; with it being constantly at such a fever pitch, more dynamic range and more moments of rest and quiet were called for to enhance the moments in the film where a feeling of scale or terror was most called for.

The Mystery of the Snake and the Mermaid

There's also a snake that appears occasionally in the film, our “guide” of sorts as Škarnulytė states in her introduction on the night. The snake – after stealing the show in a great scene where it wriggles over the control console of the nuclear power plant – sheds its skin in the last scene, after archival bomb blast footage plays out.

Trying to figure out what this snake could mean seems the wrong approach, yet when cinematic symbolism slithers across the screen, who can resist the temptation to undertake such an analytical task? Is the final scene, when it sheds its skins after mushroom clouds begin to form, the film itself telling us that the snake betrayed us? Did it convince one of the technicians to plug the nuclear power plant back in and it blew up? Is the snake warning us about our new sun god – nuclear fission – and that these cathedrals to its power occasionally blow up?

In a shot towards the end of the film, we see Škarnulytė swimming in the ocean, dressed as a mermaid. This act has become a kind of signature for the artist and can be seen, for example, also in her film Sirenomelia from 2016. In fact, this is maybe even the most entrancing and captivating scene in the whole movie. But, again, what does it mean in the context of this film?

The snake and the mermaid are similar both non-human, folklorish characters introduced into a film which takes on the documentary form. Their inclusion in this film however produces the same problem but for opposite reasons: if the snake suffers from an overabundance of interpretive possibilities, the mermaid figure suffers from a scarcity of interpretive possibilities in any symbolic matrix at play.

Where did the mermaid come from, and why did she appear in this film? The interpretative problem with the mermaid seems to be that it is a very specific internal reference with the catalogue of Škarnulytė, and any meaning seems hidden and cryptic; simply, a mermaid figure does not have the same level of archetypal depth as a snake does. And if it was not for Škarnulytė’s statement that this snake was our “guide” (and presumably, neutral, therefore) and drawn from Lithuanian mythology (a fertility symbol, a less devious idea of the snake) I would have assumed that this was the typical archetypal malicious snake from most Western mythology in our midst, here to be a faulty companion on our journey through the architecture. It is a yellow and black python afterall. Nothing this snake does or does not do, ties it to any clear interpretation of the snake; it just is – often just slithering or swimming around – leaving its real motivations (if it has agency at all) or meaning unclear.

One could take against the first half of the film and say it relies too heavily on a form of cinematic fetishism: long shots over old technology. Therefore, as the second half of this film plays out, these intrusions of the snake and the mermaid into a quite straight voice-over free documentary do break the “oppressiveness” of the gaze of the film’s first 45 minutes, moving the film into more allegorical territory. However, whatever allegory is at play, is opaque to read. The scenes in which these characters appear are certainly some of the most aesthetically interesting in the whole film, but are these moments of aesthetic delight and mystery worth the trade-off in greater conceptual coherence?

Learning to love the Spectacle

As the final words on screen “We Stand With Ukraine” remind us – with Russian and Ukrainian troops perilously close to certain nuclear power plants within Ukraine – the risk of another disaster on the scale of Chernobyl is now suddenly a real and present danger again. However, Burial does not get into the complexity of the argument about the merits of nuclear power. Burial is, for me at least, a melancholic film. It is most powerful as a tribute to the achievements of an earlier age of scientific and societal ambition, perhaps a more frightening age granted, but at least an age of trying to tame incredible forces for the betterment of a people (at least on paper, of course).

The feeling of needing to decode seems innate and as ingrained in my watching habits now – as much as my suspicions of snakes whenever one suddenly appears in a story. So how does one square these fairytale-like characters into a film about nuclear power? This is the question I wrestle with. But perhaps, as the saying goes, one should stop worrying and learn to love the spectacle.